On May 19-20, the Fourth Annual Forum of the EU Mission on Adaptation to Climate Change concluded in Wrocław, gathering a wide array of European leaders and organizations dedicated to climate resilience. REGILIENCE, through our key partner FEDARENE, was pleased to be present at the event, supporting the shared commitment to advancing climate adaptation efforts across the continent.

The EU Mission: fostering local climate action

The EU Mission on Adaptation to Climate Change stands as a crucial strategic initiative, empowering European regions, cities, and local authorities to enhance their preparedness for climate change impacts. The annual Forum, co-organized by the European Commission and the Polish Presidency, is a pivotal event. It is designed to showcase concrete adaptation measures from regions and cities, facilitate in-depth discussions, and share innovative tools and solutions emerging from various Mission-aligned projects. This year, the spotlight was firmly on practical, inspiring examples of how communities are addressing specific climate challenges. The Mission Forum’s rich and insightful agenda, including hands-on site visits in Wrocław and a specialized Pre-Forum Workshop for the Community of Practice, provided invaluable opportunities for practical learning and exchange.

FEDARENE’s presence at the Forum offered a valuable opportunity to informally share insights about REGILIENCE during networking discussions, highlighting its approach to supporting adaptation at local and regional levels.

While not part of the formal programme, our presence at the Forum allowed us to:

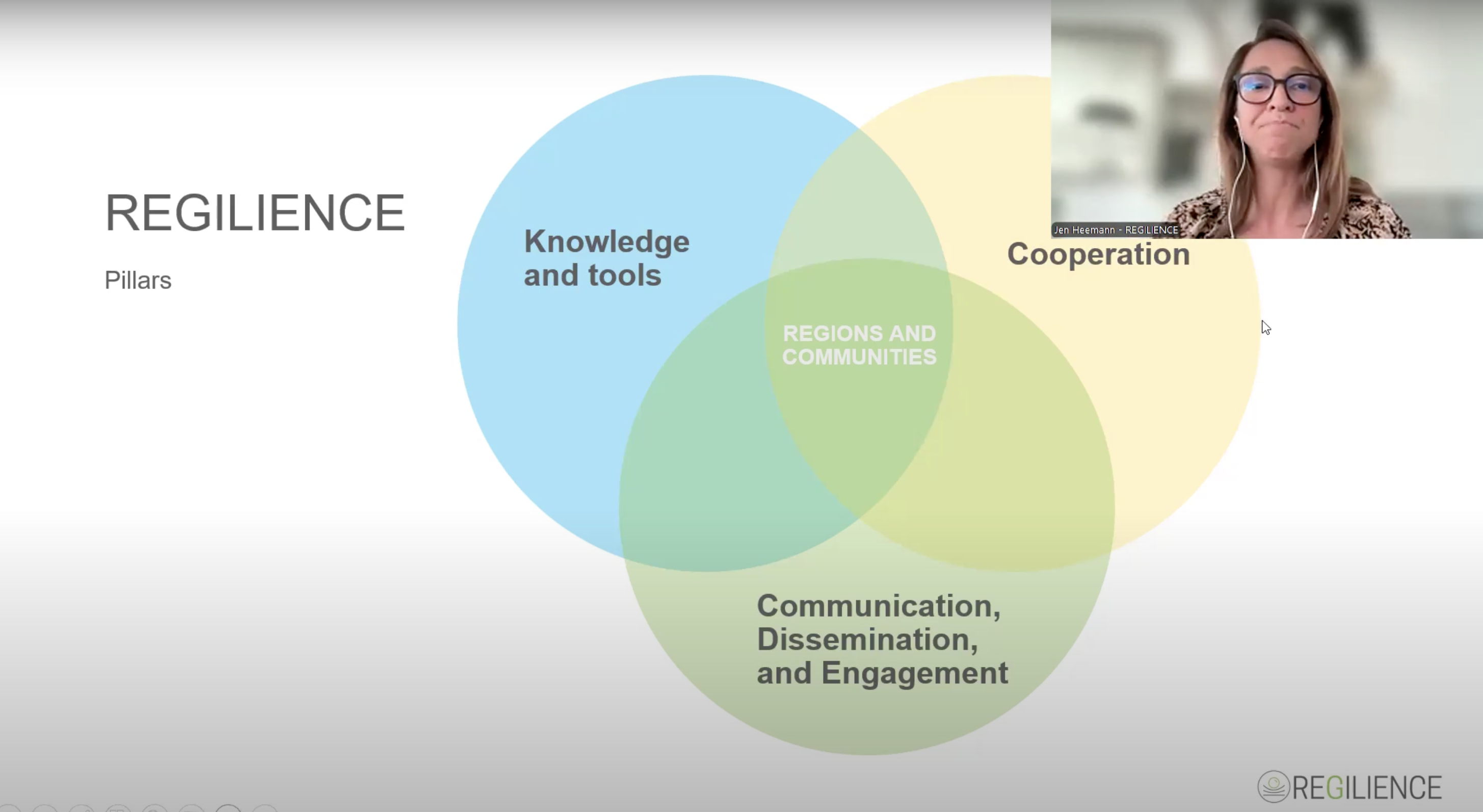

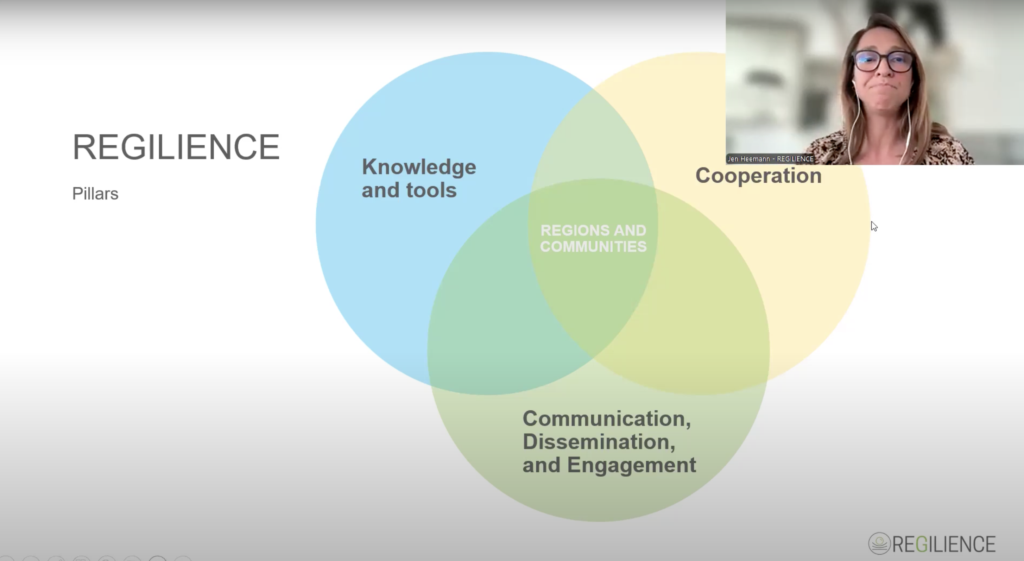

- Introduce the REGILIENCE mission: During informal exchanges, we took the opportunity to briefly convey the project’s overall goals and strategic approach to helping communities strengthen their climate resilience. These conversations offered a clear snapshot of our contribution to the broader adaptation effort and helped situate our tools and activities within the Mission’s objectives.

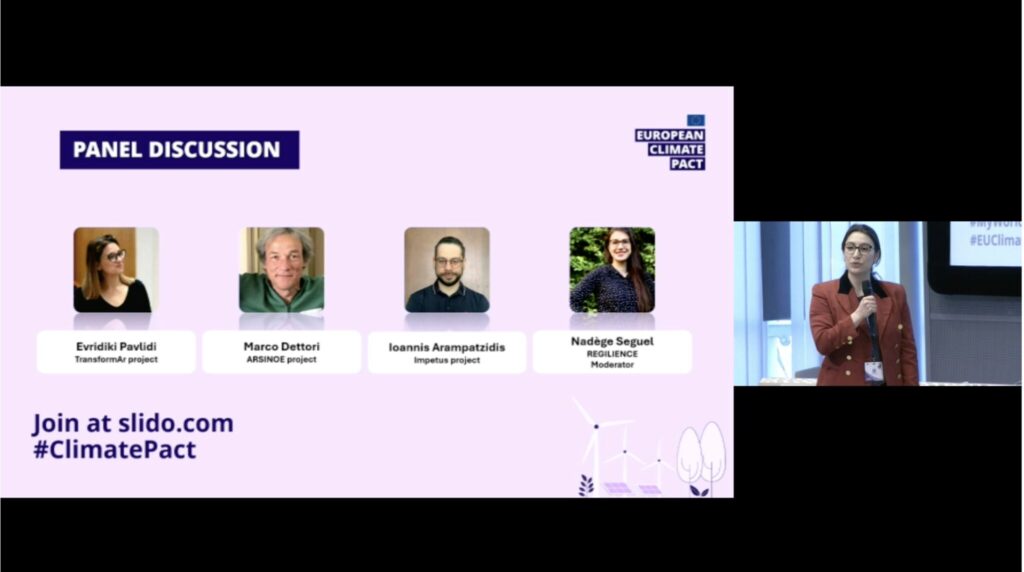

- Present our new Quick Guide” on Natural Hazards: As part of the Forum’s poster exhibition, we had the opportunity to showcase our newly launched series of Quick Guides, developed in collaboration with our sister projects ARSINOE, IMPETUS, TransformAr, and Pathways2Resilience. These practical, accessible guides offer local and regional authorities clear, actionable insights on how to prepare for, respond to, and build resilience against increasing threats from natural hazards like floods, heatwaves, storms, and wildfires. Designed with infographics, checklists, and case studies, they serve as tangible tools for action, directly supporting the Forum’s emphasis on practical solutions.

Shaping the future: Key learnings and sustained commitment

Discussions throughout the event consistently underlined several critical themes: the absolute necessity of multi-stakeholder collaboration, the urgency of viewing adaptation as a top priority, the importance of learning from best practices to avoid maladaptation, the strategic value of investing in prevention, the ongoing need for adequate financing, the imperative of multilevel governance coupled with strong citizen engagement, and the inherent interconnection between adaptation and mitigation.

REGILIENCE’s ongoing commitment to supporting Europe’s climate adaptation goals drives us to continuously refine our tools, strengthen support to regions, and contribute to building a more resilient and connected climate adaptation community across the continent. Alongside our project partner FEDARENE, we engaged in networking and discussions that provided important insights to help advance these efforts.