From 25 to 27 June 2025, the 12th edition of the European Urban Resilience Forum (EURESFO), co-organised by REGILIENCE, ICLEI Europe, the European Environment Agency (EEA), the City of Rotterdam and a wide network of partners, brought together city and regional leaders, practitioners, and institutions to exchange on how to accelerate local climate action and resilience across Europe. This year’s forum placed particular emphasis on accelerating resilience action, community-driven approaches, polycrises, and multilevel cooperation: themes that resonate deeply with REGILIENCE’s mission.

Setting the stage: REGILIENCE pre-EURESFO workshop

In the lead-up to the main Forum, REGILIENCE hosted a hands-on workshop designed to help local and regional actors deepen their understanding of climate hazards and innovative adaptation funding strategies. The workshop was structured in two parts and moderated by Nadège Seguel and Federico Aili (REGILIENCE).

The first session “Addressing main hazards” brought together diverse experiences on how local authorities are managing key climate risks. Jasper van Lieshout (IMPETUS) opened with a presentation on flood adaptation. This was followed by a joint contribution from Tereza Hnátková (CZU Prague) and Sanna Varis (City of Lappeenranta, TransformAr), who presented nature-based approaches to managing stormwater risks in Finland. Pauline Guérécheau-Desvignes (ADEME Guadeloupe, TransformAr) concluded the session with insights into drought adaptation in Guadeloupe, highlighting the Local Adaptation Fund (FLAG) as a replicable funding mechanism for resilience in outermost regions.

The presentations were followed by small group discussions organized per topic. Each expert led a table, supported by a facilitator from the Regilience team, to guide the discussions. There were two rotation rounds, allowing participants to join two out of the three topic tables—droughts, storms, and floods.

Key highlights from the discussions included:

- The crucial role of technology in providing actionable data to support better decision-making.

- Multi-level coordination and funding were identified as persistent challenges.

- The agriculture sector was highlighted as particularly vulnerable, often deemed unbankable under current financial standards.

- Across all topics (droughts, floods, and storms) a lack of awareness was seen as a barrier, pointing to the need for better connection between knowledge and implementation.

The second part focused on innovative financing for adaptation and particularly on unlocking public-private cooperation for climate resilience. Conrad Landis presented financial tools and models developed in ARSINOE and IMPETUS projects. Afterwards, Fani Gelagoti (Grid Engineers) delivered a presentation on the role of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in building climate-resilient infrastructure. The presentation was followed by a group exercise on risks allocation mechanisms between the public and the private party.

Highlights:

- Climate considerations should be embedded in all phases of the PPP process (selection, appraisal, structuring and tender). Climate resilience KPIs are critical to establish measurable performance standards and achieve climate adaptation objectives.

- The allocation of risks (including risk-transfer mechanisms for climate risk) between the public and the private sector should be based on risk typologies and follow principles such as control and influence, ability to predict/mitigate risk, and cost efficiency.

- PPPs are a promising entry point to mobilisze private finance in adaptation but include complex agreements and negotiations which make it difficult for local authorities. Profitability (stable revenues and financial returns) remains critical for the participation of the private sector.

Heads up to EURESFO 2025

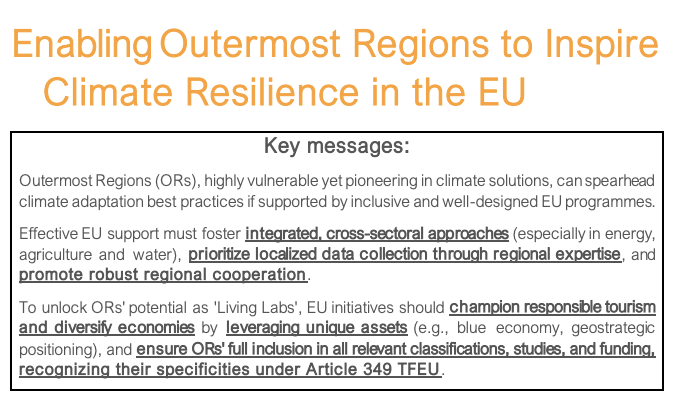

REGILIENCE also featured prominently in the high-level session “Outermost Regions Driving Climate Resilience in the EU”, moderated by Erika Palmieri (ICLEI Europe). After the key policy messages from the EU Outermost Regions presented by Nadège Seguel (FEDARENE), the panel brought together Pauline Guérécheau-Desvignes (ADEME Guadeloupe), Patricia del Mar Caro Ruiz (University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Prisca Haemers (DG RTD, European Commission), and Chiara Savina (Ecorys). Together, they explored how outermost regions are designing and implementing place-based, systemic strategies for resilience — despite their unique geographic, economic and climate-related challenges. The session reinforced the importance of context-specific approaches and the need for inclusive governance mechanisms that empower local communities.

Moving forward

EURESFO 2025 confirmed that building climate resilience requires more than technical expertise: it demands cooperation across governance levels, knowledge transfer, and inclusive approaches that empower local actors. REGILIENCE remains committed to supporting this ecosystem by developing accessible tools, promoting peer learning, and bridging innovation with implementation.